Book Manuscript

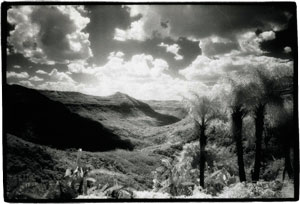

THE VALLEY OF LAMENTATION

João Biehl

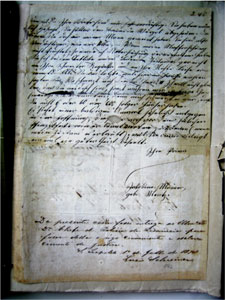

We colonists want to let Your Majesty know how much we have suffered, not just from our neighbors who are rowdy and conniving, but also from the very authorities of this district who have been protecting the wicked. . . . And so they insult us wherever they meet us, directing obscene words to ward us off, whipping some, throwing stones at others without any reason. . . . They cut to pieces the white clothes belonging to the peasant Nicolau Barth, which were hanging in the yard. And they cut the tails and manes of five horses.

Letter from the so-called Mucker to Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II, 1873

The indignation against the Mucker is so immense that the officers couldn’t hinder the corpses’ mutilations by colonists and soldiers. Someone cut off the head of Robinson and brought it to São Leopoldo in a bag. Another man carried the ear of a Mucker in his hands. The persecution of the Mucker continues until all have been hunted down.

Karl von Koseritz, Deutsche Zeitung, 1874

In heaven there is no more suffering, perishing and death, there our desires are dried up into an eternal reencounter.

Tombstone, Cemetery of Linha Nova, circa 1870

“Home is where one starts from.

[…]

And the end of all exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

T.S. Eliot, The Four Quartets

The Mucker War

The body of a beheaded woman was found in May 1993 in the woods near São Leopoldo, the first German colony founded in 1824 in the southern province of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. As if the brutal killing wasn’t bizarre enough, the stories that explained her death were equally strange–they speak to a history of violence in that region.

Local newspapers reported that very little was known about the beheaded woman’s identity, aside from her dark skin, her scar from a caesarean section, and her age of roughly thirty years. No fingerprint matches could be made, and her head was not found. The local police chief, in a peculiar move, ordered a dummy to be dressed in the victim’s clothes “so as to rouse the memory of the people.” Someone might recall having seen a woman dressed similarly, he reasoned, and “might then contact us” (Jornal NH 1993).

This story was also mentioned in Zero Hora, the province’s main newspaper, in a report on the increasing number of homicides in that relatively prosperous region (ZH 1993). The report stated that the violence originated in metropolitan- area slums now occupied by the legions of unemployed migrants looking for work in local shoe factories, and that middle-class citizens were now building walls around their homes and arming themselves. One reporter went so far as to associate that “migrant violence” with a phantasmatic reoccurrence. A headline read, “Violence Is Resurrected in the Land of the Mucker.” For over a century, the word “Mucker” has signified sectarian fanaticism, communal breakdown, and murderous violence in the region.

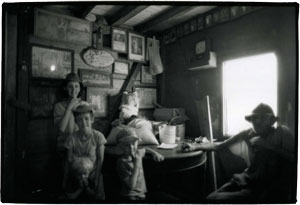

Following independence from Portugal, the new imperial administration founded the colony of São Leopoldo for some two thousand German immigrants. Given external pressures (mostly from Great Britain) and the urgency to feed a growing urban population, the country needed to find alternatives to slavery and to diversify its agricultural production. Then and in the following decades, thousands of German peasants, Lumpenproletariat, and former prisoners were recruited with promises of land, full-fledged citizenship, and religious rights, none of which would be fully granted. In this Catholic land, Protestant baptisms and marriages had no legal significance; the colonists also had no rights to participate in local administrations. Overall, the history of the São Leopoldo colony epitomizes the makeshift ways in which the plans for Brazil’s modernization have again and again been structured. They are attempts to follow external models and coexist with oligarchic modes of control (Brazil was the last country in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery in 1888). In reality, plans are only partially carried out, and people have to invent infrastructures parallel to the state in order to guarantee their survival.

Available statistics say that some five million Germans entered Brazil between 1819 and 1947.Until the 1840s, the colonists were subsistence farmers, but that would change as agricultural products began to find their way into the thriving markets of Porto Alegre as well as those of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (following a coffee plantation boom). By the late 1860s, the region was prospering, attracting investments from Britain (for railroad construction) and imports from Germany (a range of industrialized goods, from nails to textiles to champagne). Lutheran and Jesuit missionaries came as well.

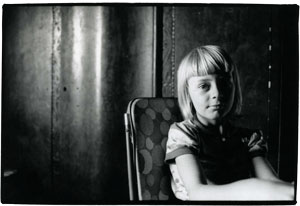

In its coverage of the 1993 beheading story, Zero Hora reported that around 1872 a group of second-generation German-speaking colonists, from various social ranks, began to be singled out as “Mucker” (meaning very religious, stubborn, and hypocritical people) by their neighbors and local authorities. For several years, people from all over the region had been meeting peacefully around the teachings of Jacobina Mentz Maurer and the herbal medicine prepared by her husband, João Jorge Maurer. Most of them were Lutherans, but Catholics also attended the meetings. According to the newspaper, the Mucker were led by “a woman suffering from psychological disturbances.” Local clergy prohibited parishioners from witnessing Jacobina’s trances, as she was said to be interpreting the Bible in a messianic way and engaging in adultery and civil disobedience. According to the newspaper, the ostracized Mucker sought revenge by ambushing local authorities and by burning down neighboring homes and trading posts. The report noted that the army was justifiably called in to respond to the Mucker’s deadly actions and to restore order.

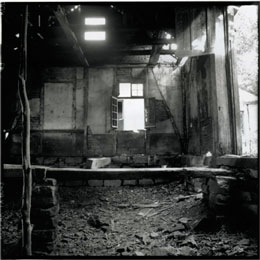

Military records show that the Maurers’ house was attacked and set on fire on July 19, 1874. Dozens of men, women and children died in the attack, as did Colonel Genuíno Sampaio, who led the provincial and imperial troops, aided by locals. Several Mucker survived and were taken to prison. Seventeen of them, including thirty-three year-old Jacobina and her newborn child, escaped and hid the nearby woods. Two weeks later, the group was found and killed. Soldiers and colonists mutilated the dead bodies–Jacobina’s mouth was slit–and placed them in a common grave in the woods. The body of João Jorge Maurer was never found. “Mucker” became a curse word and a heuristic for violence and impunity–a continuous legend of the present.

Omitted from the Zero Hora report is the fact that the military action against the Mucker was sponsored by the Germanist upper class living in the capital Porto Alegre (then Brazil’s fourth-largest city) and was silently supported by the religious authorities, newly arrived in the region. Karl von Koseritz, a Freemason philosopher and politician who also directed the influential newspaper Deutsche Zeitung (DZ), spearheaded the anti-Mucker campaign. In reference to the Mucker, Koseritz wrote, “These swindlers don’t deserve citizenship. They adore as Christ a woman who with good reason should be considered a Babylonian whore. For this band there is room either in the penitentiary or in the mad house. They have spread over society like a deadly poison. If the government does not liberate society from this monster, the inhabitants of the colonies will themselves seek justice by lynching. Deaths will come” (DZ 12/10/1873).

At the peak of the armed conflict, the Deutsche Zeitung‘s editorial read, “The Mucker have to be banished to a land where there are still cannibals. We have to treat them humanly: at deportation we should give the Mucker guns and ammunition. They would then have the opportunity to satiate their death instinct while killing cannibals, and the cannibals would have the pleasure of having Mucker for breakfast. In this way, we would help the Mucker as well as the cannibals” (DZ 7/22/1874). Meanwhile, members of the local German Society for Gymnastics and Hunting had taken over the civic guard of Porto Alegre: “We want to prove to the Brazilian government as well as to the other nations that we by no means share the sentiments of those [criminals] who call themselves our compatriots. On the contrary, we desire to contribute to their extermination” (letter to the President of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, 7/2/1874)

Immediately after the war, Koseritz (under the pseudonym C.M.S.) published a report in the German magazine Die Gartenlaube entitled, “Jacobina Maurer, the Feminine Christ, amidst the Germans in Brazil.” The Mucker events should interest the aufgeklärte Deutschen (enlightened Germans), he wrote: “How could a noncultured and libertine woman as Jacobina–who does not read anything which is handwritten and only reads with difficulty what is printed–have gained so much influence over a high number of honored and hard-working men? One is tempted to believe in a certain form of mental alienation, as we can find reference in the reports of the horrendous times of the trials against the witches. . . . It is unfortunate that in spite of all the progress of humanity, an individual can still fall so deeply into the superstition of backward times. We deplore the fact that what the poet Schiller wrote still survives today: “The worst of all horrors is man in his illusion.”

Crossroads

“[A] large acquaintance with particulars often makes us wiser than the possession of abstract formulations, however deep,” wrote William James in the opening pages of his 1902 book The Varieties of Religious Experience. I take James’s words to heart in my historical ethnography of the Mucker war. I am interested in how European notions of belief, rationality, and progress migrated to and became culturally ingrained in this periphery and in how individual subjectivity and social life there were remade through war. Beyond organized religion, I ask, what were the concrete expressions of the religious temperament, and which principles of common sense made them intelligible and socially acceptable at that time? Which forms of human agency and ideas of the sacred and of the public good did lay theology convey? When and how does popular religiosity attain political dimensions?

The Valley of Lamentation is based of original archival research in Brazil and in Germany (in state, church, medical, press, and family archives). In the book, I explore how a transplanted Germanist bourgeoisie (hiesiges Deutschtum) used science, media, and institutionalized religion to stigmatize and eventually eradicate a charismatic cult popular among fellow immigrants. I chronicle how ordinary spiritual and therapeutic practices got entangled in shifting frames of reason and power, and how the public display of these practices as fanatic and sectarian ultimately became the conduits of changes in social structures and experience in that local world, making possible something that did not exist before. The making and purging of the Muckers by the Brazilian army was part and parcel of a modern experiment of governance via the imposition of ethnicity as a category of identity, I argue. The particulars of this war can also help us to understand how, historically, transcendental values have been banished from political life in Western frontier zones.

I am drawn to the ordinary dynamics of human interactions in which Mucker, the category and the person, came into existence hand-in-hand. I want to unearth the raw materials of the moral imagination in which Mucker became the negative, the “demonic” uncanny double, so to speak, of a German-like kind of person. In this context, for reason to rule life, representations had to literally become truth in the flesh of the Other. With the violent encroachment of a German identity also emerged a sense that things could have been otherwise, that a certain way of knowing oneself and the world was now a devalued currency. I want to bring to mind the intensity of such a loss experienced in the flesh-and-blood of the so-called Mucker. Ultimately excluded from social life, the trace of their existence remained nonetheless embedded in the new Kultur grid.

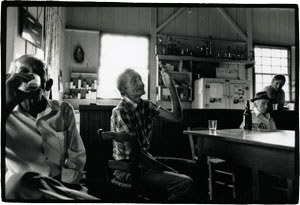

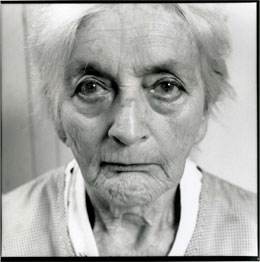

I recently located the records of the court proceedings against some of the Mucker leaders who survived the military attacks. These records have helped me to sketch the legal order that ensued after the war and that ensured the proper confinement of religious expression. They also enabled me to explore how impunity was built into this legal order and allowed for continued human exploitation. Interviews with local historians and with elderly people who recollect the war’s aftermath illuminate the Mucker as an enduring secular myth to be reckoned with and that erupts here and there as indices of the inexplicable, undesired, or unendurable in contemporary events, be they personal or collective. In academic circles, scholars insist on retelling the Mucker story in ways that cement their own epistemological subservience.

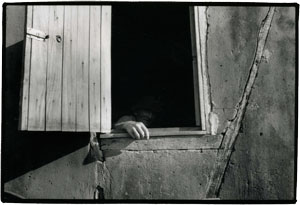

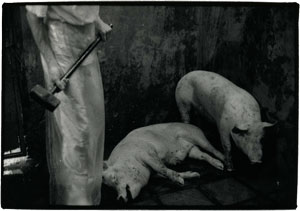

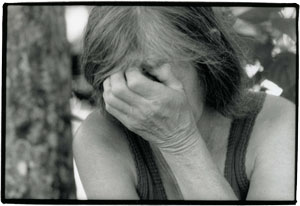

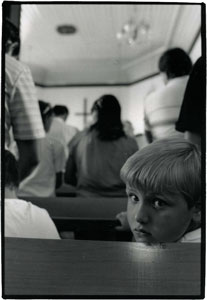

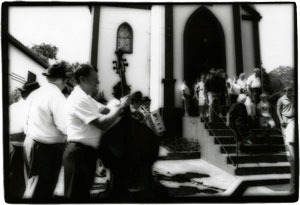

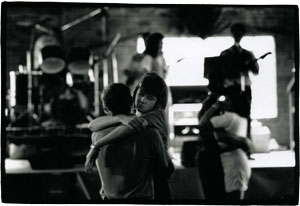

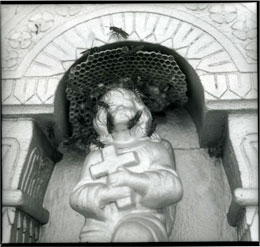

I collaborated with photographer Torben Eskerod on my two previous anthropological books (Vita 2005 and Will to Live 2007), and he will produce the visual component of this monograph as well. Torben has already joined me once in the field in connection with this project and photographed remnants of the Muckers’ material culture (ruins of homes and houses of worship, gravestones, documents, and memorabilia) as well the people from whom I collected stories about the war’s aftermath.

In the book’s conclusion, I bring this historical ethnography into dialogue with current debates on the tensions between secularism and political theology. In the case I examine, the separation of religious questions from political ones was not solely a conceptual dispute. It required an actual war, which, in turn, cemented exploitative relations between the “enlightened urban” and the “primitive rural.” I am concerned with how the devaluation of autonomous symbolic orders (a negative political theology of sorts) has become the hallmark of secular projects and with how the political subjectivities of ordinary people have been constituted around such erasures. This project sheds light on how the histories of the Old and New Worlds have unfolded in tandem, and it uses anthropology and religious studies rather than political science to understand the modern nature of religion and its relation to social and political life. Seen from this perspective, Christian political theology and modern political philosophy are not just opposing modes of thought. They are symbiotic with one another, and they are experiments in living. I believe that a critical rendering of the particulars of this “enlightenment story” can illuminate crossroads in institutional and personal decision-making and thus reveal dismissed human potentials as well as alternative approaches to the conduct of political life.